Chapter 4: Detention, Healing, and Reputation

For fighting at the academy, Ben got two weeks of detention, while Natalie and I were taken back by the First Lady to copy passages as punishment.

In D.C., discipline came in the form of endless writing—no more paddles or dunce caps, just cramped hands and growing boredom. We sat at an antique desk in a study lined with history books, scratching out lines until our wrists ached.

Even though her own grandkids were the ones who got beat up, the First Lady didn’t seem that mad.

I expected her to yell, but she just stood by the window, watching the city lights flicker. Maybe she saw something of herself in us—rebellious, stubborn, unbreakable.

By the flickering lamp, she stood by, watching Natalie and me write. She looked at mine and nodded, satisfied: “Aubrey’s writing is pretty good. The teacher says you two are working hard at the academy.”

She smiled at my neat cursive, her lips twitching upward. For a moment, I felt like I’d passed a secret test.

But when she moved behind Natalie, her face changed.

The mood shifted. She sighed—a sound that said, “Here we go again.”

I peeked over quietly.

Natalie’s pencil grip was tense, and she looked ready to bolt. I bit back a giggle—at least I wasn’t the only one struggling.

Natalie started out calm, but soon her hand was shaking, and her paper was a mess of crooked lines.

Lines slanted like a roller coaster, letters squashed together. Natalie winced, tongue sticking out as she tried to fix her mistakes, but the damage was done.

The First Lady was silent, finally getting it.

Her eyes softened. She didn’t say a word, but her frown disappeared, replaced by something like understanding.

Ben had mocked Natalie’s handwriting, gotten into a fight, and ended up in detention.

I realized it wasn’t about ink on paper; it was about pride. Natalie cared—maybe too much.

Now it looked like he had a point.

I glared at my own page, wishing I could fix everything with a few neat sentences.

We copied passages until late before the First Lady let us go.

The desk lamp cast long shadows. I felt my eyes droop, the world blurring into lines and loops. When we finally finished, I wanted nothing more than to collapse on my pillow and sleep for a week.

Gone was her daytime sternness. With her hairpins out and gray at her temples, she looked much softer, and she personally brought ointment for our bruises.

She entered our room in fuzzy slippers, her bun undone, holding a small glass jar. The ointment was homemade—maybe something from her own childhood. She hummed as she dabbed, her hands gentle.

The medicine stung. She dabbed ointment under my eye, her hands as gentle as if she were patching up a scraped knee on the Little League field. The sharp smell made my eyes water.

It smelled like eucalyptus and old memories. I flinched, but she patted my cheek and smiled, her eyes crinkling at the corners.

She was gentle, but she still scolded us: “You two little monkeys, fighting again. Next time, remember this.”

Her scolding was more habit than anger—a ritual she probably performed with her own grandkids. I felt oddly cared for, even while being chided.

After me, she went to Natalie. Natalie squirmed as the ointment went on her stomach, laughing and wiggling, nodding quickly.

Natalie’s giggles bounced off the walls. “I’ll remember, ma’am, please, it tickles, ha ha…”

Even the First Lady had to laugh in the end.

Her laughter was softer than I expected, the kind that lingered in the air and made the whole house feel lighter. For a second, we were just a trio of women—no titles, no scandals, just family.

We copied passages in the East Wing for two weeks. We weren’t grounded, but we were bored out of our minds.

Our room overlooked the garden, and we could see squirrels chasing each other in the trees while we slogged through line after line. I dreamed of escaping—running barefoot in the grass, sneaking cookies from the kitchen.

Natalie always tried to sneak out, but the First Lady caught her every time, so she got two more passages to copy.

She’d try the old “cat in the window” trick or the classic “bathroom escape,” but somehow the First Lady was always one step ahead. “Nice try,” she’d say, handing Natalie another stack of paper.

When I finished mine, I helped her with hers, giving her a look full of fake outrage.

I huffed and puffed, pretending to be annoyed, but secretly glad for the company. Natalie grinned, mouthing, “Best study buddy ever.”

By the time we were finally done, two weeks had gone by. I’d copied so much I could barely see straight.

I stretched my fingers, rubbed my eyes, and swore I’d never complain about homework again. The halls of the East Wing seemed to sigh with relief as we were set free.

On our first day back at the academy, as soon as we walked in, the noisy hall went dead silent.

It was like a scene from a high school movie—the wild kids returned, and everyone held their breath. I caught a few whispers, and someone dropped their lunch tray with a clatter.

Natalie grinned at me, full of mischief: “See? I told you, stick with me, you’ll never get pushed around.”

She winked, looking as if she’d just won a prize fight. I rolled my eyes, but inside, I felt a spark of pride.

We weren’t getting pushed around, but our classmates were probably terrified. We’d taken out three VIP kids our first week—they must think we’re wild animals.

Rumors flew—some said we were CIA plants, others that we’d broken a senator’s nose with one punch. I kept my head down, but inside, I kind of liked the new reputation.

I managed a crooked smile.

Natalie nudged me, and I let myself grin back, feeling a little less out of place.

Ben shrank into a corner, muttering, “You two are impossible. I don’t want to hang out with you, only jerks and…”

He glared at us, then at the scuff mark on the wall. I almost felt sorry for him—almost.

Before he could finish, the boy next to him gently patted his shoulder and shook his head: “Ben, not cool.”

The new boy’s voice was calm, his presence soothing. He wore a blue sweater vest and had the easy confidence of someone used to smoothing ruffled feathers.

Ben seemed close to him, and though annoyed, he shut up.

It was a small victory—one fewer enemy, maybe even a future ally.

Natalie’s seat was next to his. After sitting, this handsome boy gave us a polite nod and smiled: “I’m Caleb Sanders, from the Sanders family—Ben’s study buddy.”

He offered a handshake, warm and steady. Natalie took it, her cheeks faintly pink. For the first time, she was speechless.

Even Natalie couldn’t turn down a friendly face and nodded back.

She recovered quickly, flashing a grin. “Nice to meet you, Caleb.”

After that, no one at the academy dared mess with us.

It felt like the rumors did all the work for us. We walked the halls unbothered—no more shoves, no more name-calling. Even the teachers seemed to keep their distance, half-amused, half-afraid.

After a few days, I finally relaxed.

I started to breathe easier, swapping my anxious glances for actual smiles. Natalie started humming under her breath, a sure sign things were looking up.

There were a lot of rules in D.C., easy to break, but the academy was peaceful.

The list of do’s and don’ts was long—dress code, curfews, approved websites—but somehow the place felt safer than I’d expected. Nobody really cared where you were from as long as you played by the rules.

The Vice President’s son and ambassador’s daughter, siblings, were easy to get along with. Among our classmates, there was a shy girl named Lillian, who soon became our friend.

Lillian wore oversized sweaters and always smelled like lavender. She loved books, always had a novel peeking out from her backpack. We clicked instantly—three’s a crowd, but four’s a party.

Whenever there was something new, the Vice President’s son would bring one each for his sister, Natalie, me, and Lillian.

He’d show up with the latest fidget gadget or a stack of tickets to a new museum exhibit, always thinking of us first. It felt like we were finally part of a crew—a little D.C. family of our own.

Ben was always lively, constantly bumping into things, showing up with a bruise on his forehead and making Caleb do his homework.

His antics were legendary. He once tried skateboarding down the hallway and crashed into a teacher’s desk. Caleb would sigh, but always help him out of trouble, like a patient older brother.

The quietest in class was the fifth kid, who sat in the corner and barely spoke, sometimes startling people.

Her name was Rebecca. She had thick glasses and a notebook full of mysterious doodles. When she did speak, it was always the smartest thing said all day. Natalie swore she was secretly a genius.

The First Lady’s attitude gradually softened.

She stopped treating us like walking disasters and more like her own grandkids. She’d leave notes in our lunchboxes—reminders to wear a jacket, encouragement before big tests.

When we messed up, she just scolded us: “You grew up in my house, just like my own grandkids. Do it again and there’ll be consequences.”

But even her threats were losing their bite. I realized she cared for us—not just as obligations, but as family.

But she could never bring herself to punish us too hard.

She’d stomp her foot and wave her finger, but we’d catch her smiling when she thought we weren’t looking. Her punishments were more bark than bite.

She was like someone who’d been alone for ages—when she finally saw two lively kids, she couldn’t help but hold us close, afraid to lose that spark of joy.

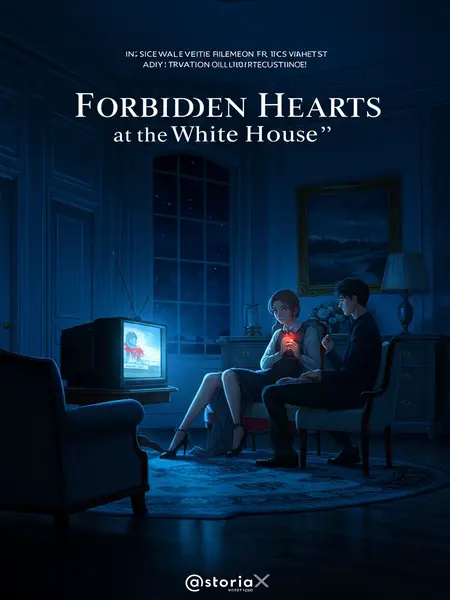

Sometimes, late at night, we’d find her in the sitting room, eyes closed, listening to old jazz records. I’d wonder what she was remembering—maybe the family she’d left behind, or the family she’d found in us.

With her help, Natalie and I slowly grew up and learned to rein it in.

We learned to think before we acted—most of the time. Savannah was still in our hearts, but D.C. was starting to feel like home, too.