Chapter 2: A Hundred Years Apart

"What about you? What's your name?" I scrawled, my pen hovering over the old page.

He wasn’t much older than a kid—his writing made that clear—and he seemed just as giddy as I was, filling half a page with his details in a rush of old-fashioned prose.

From his words, I pieced together his world: Nathan Blackwood, sixteen, son of the Blackwoods—a name I’d seen etched on old brick buildings downtown. His family ran a pharmaceutical business, patent medicines and tonics, though I had a feeling some of it was probably more snake oil than science. Born into privilege, with a little sister named Dorothy and enough money for prep school. Old money, the kind with summer homes and servants.

"Are you really from a hundred years in the future? What's it like there?" Nathan’s letters crowded the margin, his excitement obvious even without seeing his face.

I paused, pen tapping against the desk, trying to put a century into words he’d understand: "A hundred years later, there’s no war here. America’s peaceful, prosperous. Every kid goes to school, rich or poor..."

I wrote about televisions—"like a movie theater in your living room"—refrigerators that keep ice cream frozen all summer, airplanes that crisscross the country in hours, and trains that blur past at a hundred miles an hour. Nathan couldn’t picture it, so I sketched a chunky airplane that looked more like a chicken than a jet, but he got the idea.

Every new invention brought a flood of exclamation marks from him—sometimes three in a row. I couldn’t see his face, but I could just imagine the look, the way my students light up when I announce a snow day.

"How wonderful!" Nathan scribbled. "A hundred years later is actually like this. Electric lights in every home! Automobiles for regular folks! I wonder if I'll live long enough to witness it with my own eyes!"

My pen froze. He was living in the Roaring Twenties, on the edge of a cliff. The Great Depression was coming—a crash, a darkness that would sweep away fortunes like his overnight.

My teacher’s instinct screamed to warn him. But what if changing the past made everything worse—like those time travel movies my students love?

Nathan didn’t seem to notice my hesitation. He wrote, "A few days ago I said I didn't want to go to school. My father grounded me for a week—can’t even go to the soda fountain with the guys."

"Why do you hate going to school?" I asked, curious.

"The stuff the teacher teaches is so boring—Latin declensions, who needs that?—and there's tons of homework. If you can't finish, you get dragged to the front and whacked on the knuckles with a ruler..." He went on and on, griping about Mr. Henderson—"That guy has it out for me, I swear. Always calls on me when I’m spacing out."

Nathan was in his rebellious phase, skipping class for cards with his buddies, sneaking into vaudeville shows at the Orpheum, and catching nickel movies. Honestly, it sounded like half my junior class.

He didn’t have many real friends—just a bunch of pals to get into trouble with—so he told me everything. His trust was almost painful.

"Rachel, I told one of my friends about you. He said I’ve gone crazy from reading too many pulp novels—Amazing Stories and that sort of trash. What does he know."

"Someone asked me to play cards, but I turned them down. They just see me as a sucker, a rich kid to fleece. Tommy admitted it when he was drunk last week."

"Today I skipped class to see the new circus downtown. There was a man from India who swallowed swords and breathed fire—wild stuff. The elephant was kind of sad, though."

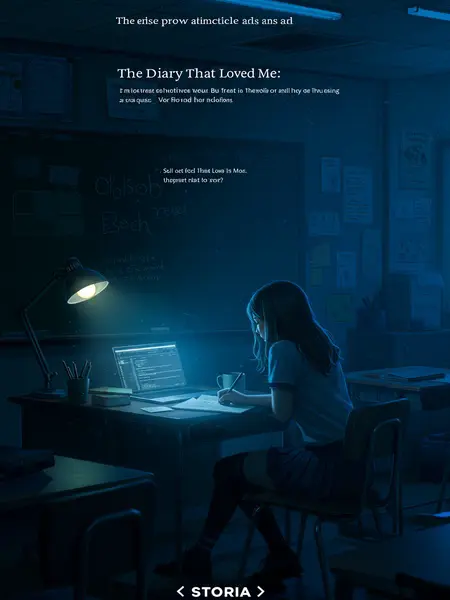

A week went by. Every night, I checked the diary, half-hoping, half-dreading what I’d find. My life was a cycle—up at 6:30, coffee and toast, drive to Franklin Roosevelt Middle School, teach five periods of history, grade essays during lunch, detention duty twice a week, home by six if I was lucky.

But now, I had something new—something impossible. Each evening, I’d pour a glass of wine and curl up on my couch, reading Nathan’s latest. Sometimes his stories made me laugh—like the time he tried to impress a girl at a dance and stepped on her toes so much she hobbled away. Other times, my heart clenched with worry. Black Tuesday was coming. How long could his innocence last?