Chapter 6: The Ginkgo Tree

"Rachel, what flowers do you like?" Nathan asked one breezy spring day.

"There’s a space in front of my yard. Mother wants roses, but they’re so ordinary."

I pictured my grandma’s garden, the leaves outside my school rustling in the fall. "I don’t really have a favorite flower. But I like ginkgo trees."

"Ginkgo? That’s not a flower."

"True, but ginkgo trees can live for thousands of years. Touching their trunk is like talking to history. There’s one at my school that’s supposed to be 200 years old."

"Then I’ll plant a ginkgo tree. Maybe a hundred years from now, you’ll see it. It’ll be like this diary—something that connects us."

I thought he was joking, but the next day he reported: "I really planted a ginkgo tree. Father thinks I’m crazy—‘Why not an oak or maple?’—but I told him ginkgos are special. He liked that."

"I carved a poem into the trunk so you’ll know it’s mine."

"What poem?" I asked, already guessing.

He wrote, each letter careful and slow:

"I only wish your heart to be like mine."

My heart twisted and dropped. Oh, Nathan.

His feelings were so open, so raw—a young man’s longing impossible to hide. The cut-out sketch, the little notes, the way he signed every entry, "Yours, Nathan."

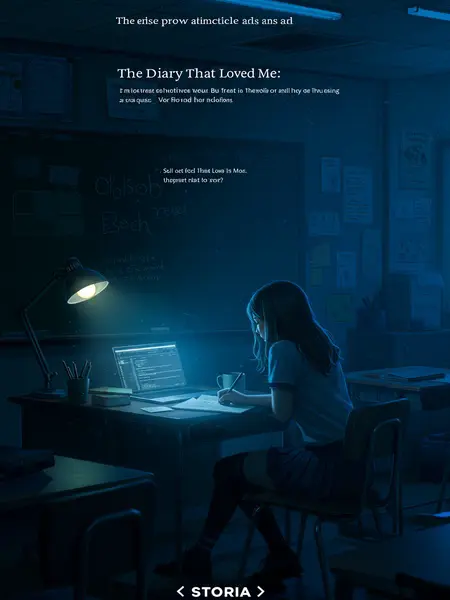

I closed the diary, pressing my palms against the cover, fighting a sudden ache. Nathan wasn’t my student, but he felt like one—a young, idealistic kid with his whole life ahead.

It’s normal for a boy his age to develop a crush on someone who’s always there for him. I’d seen it happen every semester—students falling for a teacher, a tutor, anyone who showed them kindness.

But I had to be the adult. Even across a century, I had to set the boundary.

I remembered Mr. Harrison, the handsome senior teacher at my school. When he got a love letter from a student, he came to my classroom pale as a ghost. He started dressing like a slob, talking about his (fake) wife, making himself unappealing. The love notes stopped, and his job was safe.

With Nathan, it was simpler. All that connected us was a diary. No one could accuse me of anything. If I stopped replying, maybe his feelings would fade, like a fire starved of air.

Maybe he’d move on, meet someone at Columbia, fall in love for real. There was never any real possibility between us. I couldn’t give him hope.