Chapter 7: The Words We Leave Behind

My aunt always said I was cold-blooded—my heart as icy as my father’s. "You’re just like him," she’d mutter after too many gin and tonics. "Never letting anyone in."

I guess she was right. I learned early that caring too much only led to heartbreak.

My parents were once the picture of love—so much that they named me Rachel Quinn, after my mom’s favorite aunt and my dad’s last name. It didn’t last.

Love came fast and left faster. After a few years, my dad started cheating, coming home reeking of perfume and smoke. My mom screamed, threw dishes, threatened divorce. He’d just walk out again.

When I was seven, my dad’s mistress showed up at our door, pregnant and smiling. I hid behind the stairs, watching my world fall apart.

My mom’s spirit died that day. She overdosed one night, and I found her the next morning, thinking she was just sleeping late.

At the funeral, my dad never cried—just checked his watch, eager to leave for his new life. I was left with my uncle’s family, “just for a while,” he said. Nineteen years ago.

He sent checks for a couple years, then vanished—California, maybe Nevada, no one knew. My uncle and aunt fed and clothed me, but I always felt like an outsider. I kept to myself, reading alone in my room, skipping family dinners when I could.

I chose a local state college, took the scholarship, never asked my aunt for help. She’d done enough, she reminded me often.

Now, I kept to myself. The staff tried to set me up—with the PE teacher, a cousin, the church pianist—but I always refused. They called me unsociable, destined for a house full of cats. I didn’t care.

I knew better than to chase what wouldn’t last. Better to be alone than abandoned.

So I stopped replying to Nathan.

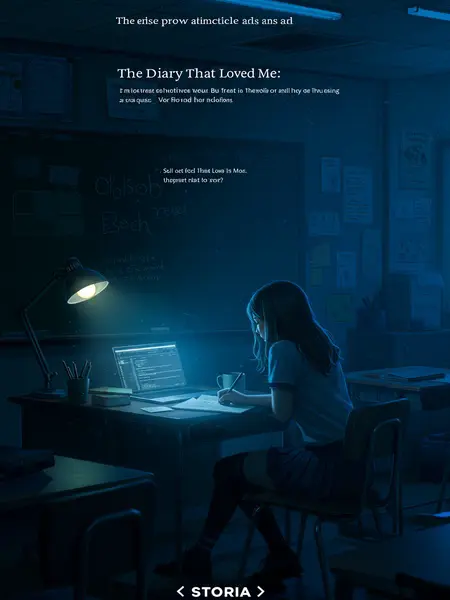

Still, every day, new writing appeared in the diary. I’d open it after work, glass of wine in hand, reading his increasingly desperate notes:

"Rachel, why aren’t you replying? Are you really busy? The teachers at my school are always busy at the end of term."

"Rachel Quinn, that poem didn’t mean anything. Don’t feel burdened. It’s just a line I liked."

"1928, July. My high school career is ending. Even Mr. Henderson shook my hand, said I’d become a fine young man."

"My father says the economy’s getting unstable—something about buying on margin—wants me to study in England. But I want to stay. I want to be near that ginkgo tree."

"Rachel! I have good news—I passed the Columbia exam! My father couldn’t believe it, said I got lucky. But I ranked in the top twenty! Me!"

"College is so different. Philosophy, literature, women’s suffrage—new friends. There’s a girl named Margaret in my English class. She has brown hair, like I imagined you do."

"Rachel, have you forgotten me?"

The last line blurred on the page, ink running like tears. I closed the diary, but his words echoed in my head. Had I really left him behind—or was I the one who couldn’t let go?